50th Anniversary of Contemporary Glass Key Information

Celebration Map

Celebration Map

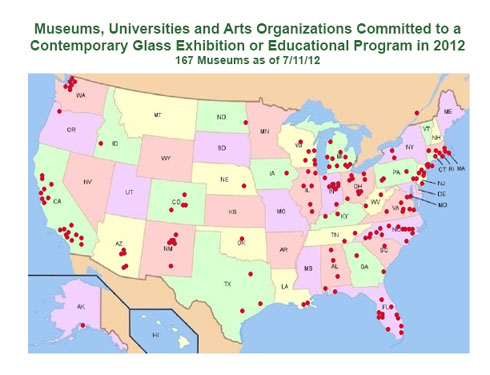

Museums, Universities and Arts Organizations Committed to a Contemporary Glass Exhibition or Educational Program in 2012

167 Museums as of 7/11/2012

Click here for a list, by state, of all the venues pictured above, as of 7/11/2012

The Midwest Contemporary Glass Art Group (MCGAG) has produced an informative publication listing and detailing all the museum exhibitions related to the 50th anniversary of the Studio Glass Movement occurring in Wisconsin, Illinois and the part of Indiana bordering Illinois. Click here to view a pdf of this document.

Testimonials

Testimonials

No testimonials at this time. Check back soon!

A Curator’s Look at Contemporary Studio Glass

A Curator’s Look at Contemporary Studio Glass

By Gerald W.R. Ward

Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

October 2011

My crash-course into the world of contemporary studio glass started one day in late 1996 or early 1997, when in the course of a chance meeting in one of the Museum’s galleries, our Director, Malcolm Rogers, suggested to Jonathan Fairbanks and I that our department might want to organize a show of contemporary studio glass in late 1997. This sounded like a great topic, although the timetable for an MFA exhibition was a bit short, especially if we were to prepare a catalogue of the show. But Jonathan quickly assented and immediately enlisted the invaluable help of Pat Warner, volunteer extraordinaire. With the assistance of the entire Department of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture, and with the key support of Dale and Doug Anderson and many other collectors and artists, Jonathan and Pat pulled it off.

“Glass Today by American Studio Artists” opened on August 13, 1997, and before it closed on January 11, 1998, it attracted more than 250,000 visitors, making it one of the most popular museum exhibitions held anywhere in 1997. The catalogue, designed by Cindy Randall, created a permanent record of seventy-four works of art made by twenty-eight artists, ranging alphabetically from Howard Ben Tré to Toots Zynsky. The Art Alliance for Contemporary Glass also lent its support to this project, marking the Museum’s first, but not the last, association with the AACG.

“Glass Today” exposed me to the amazing world of American studio glass for the first time in a serious way. Since the 1970s, I had had some curatorial involvement with contemporary silver and furniture, but had never previously focused on the magical properties of glass and the astounding versatility of the artists who work with it in the myriad ways that its unique properties allow.

A few years later, I had the opportunity to serve as the curator for the Museum’s exhibition of about 120 objects from the collection of Ron and Anita Wornick. “Shy Boy, She Devil, and Isis: The Art of Conceptual Craft” featured work in many media, including a substantial number of works in glass by American, British, and European artists. In preparing for the exhibition I had the privilege of seeing the works in situ in the Wornicks’ homes in San Francisco and Napa Valley, and was blown away by the power of glass objects to transform a domestic interior. The Wornicks’ collection includes significant objects by Dale Chihuly (of whom more in a minute), Clifford Rainey, Bertil Vallien, Richard Jolley, Maria Lugossy, Hank Murta Adams, and many others.

Several years ago, I was given the assignment by Patrick McMahon, our Director of Exhibitions and Design, of serving as the Museum’s curator for the “Chihuly: Through the Looking Glass” exhibition held to great acclaim at the Museum from April 10 through August 9, 2011. This show attracted more visitors - in excess of 372,000 - to the Museum than all but four other exhibitions in the institutions 130 year history - quite an accomplishment for a living artist, and a living American “craft” artist to boot. Our accompanying book, supported by the AACG and again designed by Cindy Randall, had to be reprinted and eventually sold out.

It was a joy to be associated with the Chihuly exhibition. Most visitors were wildly enthusiastic, often gasping as they rounded a corner in the exhibition to see the Mille Fiori display, for example. Some even squealed. People went through the show with smiles on their faces and often engaged strangers in conversation. Many people told me that, even though they had lived in Boston for years, they had never previously visited the Museum.

How to account for the slack-jawed response that the show generated? Each individual responded in their own way, but a few reactions were widespread. People were astonished at the technical virtuosity revealed by the objects, as well as by the size of many of them. The show was almost like a medieval Wunderkammer in its ability to evoke a sense of wonder and amazement. Chihuly is a notable colorist, and the colors of the pieces also elicited many favorable comments. And the seemingly inherent contradiction between the size of the objects, the complexity of the installations, and the fragility of glass also drew much commentary. It was art for art’s sake, and it was refreshing to see the public’s response to such a presentation, which people responded to viscerally but also intellectually.

At the end of the show, a groundswell of opinion led the Museum to mount a public campaign to retain the Lime Green Icicle Tower - 43-feet tall, ten thousand pounds, 2,342 icicles - as a fixture in the Shapiro Family Courtyard in the Museum. Although several donors provided large gifts that made the purchase possible, thousands of individuals contributed to the drive by stuffing bills in a donation box or texting their contributions to the Museum. It was an exhilarating and gratifying effort.

Chihuly, however, is but one of the bright stars in the world of contemporary studio glass, now approaching its fiftieth anniversary. From its origins in the workshops of Harvey Littleton and Dominick Labino through the course of the last five decades, studio glass has steadily emerged as a world-wide avenue of the arts to be reckoning with. Populated with major international artists, whose diverse work transcends the tiresome “art or craft” debate and who create sculptural forms that delight the eye and exercise the mind, the field is supported by enthusiastic private and public collectors, active support groups such as the AACG, and by many major museums. One can only wonder what the next half-century will bring.

QR Codes Promoting the 2012 Celebration

QR Codes Promoting the 2012 Celebration

Download and save these QR codes for use on any website or print materials and help promote the 2012 Celebration!

Web-Ready QR Codes:

Right-click on any of the codes to download. Or download a ZIP file of all three.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Press-Ready QR Codes:

Right-click on any of the codes to download. Or download a ZIP file of all three.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

50 Years of Studio Glass: From Black Tie to Blue Jeans

50 Years of Studio Glass: From Black Tie to Blue Jeans

By William Warmus

2012 celebrates 50 years of artists making art from glass. In 1962, the artist Harvey Littleton gathered a group of artists, craftspeople, scientists and scholars at the Toledo Museum of Art for a series of workshops that demonstrated that glass could be made into art in the artist’s studio rather than in an industrial setting: these came to be known as the founding events of studio glass.

The early workshops focused on blowing glass, although from the beginning there was also an interest among artists in all the ways glass could be used as an art medium: hot, cold, blown, cast, conceptual, abstract, realistic. Of course glass had been worked since ancient times. What gave these early workshops their defining quality was their focus on education: Littleton and others were intent upon bringing the medium of glass into university art programs, where once available, students and emerging artists could begin to make glass in their own studios. And from there, a gallery and collector base evolved beyond anyone’s wildest dreams.

Fifty years tells the story: a fiercely independent creative spirit emerged. Glass is now taught in hundreds of programs in the United States and perhaps thousands worldwide. There are dozens of prominent galleries exhibiting art made from glass, and leading museums display studio glass, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to the De Young in San Francisco and everywhere in between.

The tastemaker Russell Lynes was a juror for both the landmark New Glass exhibition in 1979 as well as Glass 1959, which showcased primarily industrially designed glass, both at The Corning Museum of Glass. He summed up the changes that studio glass ignited: “the new glass is more romantic and flowing on the one hand, expressionist and tough on the other, freer in its design, more explosive. Its costume is blue jeans not black-tie, unmoved by the forms of etiquette and the manners of formality which pervaded the glass of 1959.”

What has also emerged during the 50 years since Toledo are a series of narratives about glass as art: aside from the focus on Littleton, there are narratives about the 1950s exploration of slumped, fused and cast glass as well as the emergent role of women in what was once an almost exclusively male domain. In part what we celebrate in 2012 is 50 years of effort on all these fronts to make this incredible magical medium available to artists everywhere. Glass has truly become the new bronze, but it is also the new paint, the new abstraction, the new architecture.

“Throughout history, people have suspected that glass is magic. How else can a material be explained that imitates other materials but cannot itself be imitated?...That is hot liquid and frozen solid, transparent and opaque, common and exalted?” - Tina Oldknow, Curator, The Corning Museum of Glass.

William Warmus has been curating exhibitions and writing about glass since 1976, and is an AACG Advisory Board member.

Studio Glass Highlights Decade by Decade

Studio Glass Highlights Decade by Decade

By William Warmus and Beth Hylen

1960s–70s

- Emphasis on technology and education.

- Experimental discovery of the material through trial and error.

- Self-expression (not sales) most important.

- Male-dominated.

- Primarily hot (furnace) glass; some slumping plate glass, laminating pieces of blown forms, fusing, etc.

- Few critics.

- Emerging interest by museums: first big traveling exhibitions showcasing glass are organized.

- Earliest galleries devoted to glass open.

- Equipment: furnaces, tools, glass.

- Long-standing techniques, such as the “fuming” and “feathering” popular during the Art Nouveau period, are continually reinvented and updated, even to this day.

- Part of broader international craft movement of the 1960s in which clay, fiber, wood, and metal are used for creative expression.

- Dichotomy exists between the sculptor in search of form (the “technique is cheap” attitude) vs. the craftsman striving to create a perfectly executed functional object.

1980s

- Artists pursue narrative, political, gender issues.

- More multimedia work, combining glass with other materials (wood, metal, paint, stone).

- “Art vs. craft” debate pushes aside technical issues.

- New interest in alternatives to hot glass: pâte de verre, lampworking, kilnworking, coldworking, even microwaved glass jewelry.

- Women play increasingly prominent role.

- Art museums begin to exhibit glass in contemporary art sections, not only in decorative arts galleries.

- Move toward professionalism: artists concentrate on the business of running a studio and developing marketing strategies to create a stable livelihood.

- Camaraderie of collectors and friendly competition for the most beautiful artworks leads to a relatively stable market and the development of a glass community.

1990s

- Surge in art museum exhibitions and catalogues devoted to studio glass.

- Collectors lend/donate their collections to museums.

- Schools for glassmaking multiply throughout the United States and worldwide.

- Influence of Venetian and Czech glass strengthens throughout the 1990s.

- Levels of technical skill reach an apogee.

- Glass studios range from one-person workshops to one person directing assistants who produce the glass; teamwork becomes an accepted procedure.

- Opening up of former Soviet-bloc countries, notably the CSSR, increases exchange of information.

- Internet resources related to contemporary glass emerge.

- Glass is called the “new bronze” as artists with fine arts reputations and no or few glass skills work with skilled glassmakers to make their art: Robert Rauschenberg, Kiki Smith, Louise Bourgeois are examples.

2000s

- A new generation of artists and dealers begins to take the place of the founding generation.

- Lavish books about individual glass artists proliferate, as do sophisticated books about “how to” make glass, although late in the decade, digital or ebooks begin to replace printed ones.

- Art Expositions become a major vehicle for selling work as well as for networking.

- Economy affects the sale of glass (from 2008 forward). Studios and workshops struggle and/or close. Galleries close or change ownership.

- Copyright issues command world attention.

- Participatory glassmaking experiences for novices become prevalent, including the “Walk in Workshop” at The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY, and “Kids Design Glass” at the Museum of Glass, Tacoma, WA.

- Artists and architects use structural and other speciality glasses to create large scale walls and free standing structures almost entirely of glass.

A mature movement shows an awareness of its history including:

- 50th anniversary of the “Studio Movement” celebration in 2012.

- 60th anniversary of the Corning Museum of Glass in 2011.

- 40th anniversary of Pilchuck in 2011.

Focus on the Founder: Harvey Littleton

Focus on the Founder: Harvey Littleton

By William Warmus

Harvey Littleton is the founder of studio glass. It was a long time founding: a generation passed between conception and birth. The first object we can associate with studio glass is female: a nude torso made in 1942 by Littleton. Then the birth process was interrupted as Littleton went off to soldier in World War II and later began a career as a successful potter and educator. He was back at it again in 1958-1961, melting glass in a crude furnace he had constructed himself, carving simple shapes from small cast glass forms, blowing his first glass into objects he describes as "phallic bubbles," and using a blowpipe given him by Jean Sala in France, who because of Littleton is now seen as a precursor of studio glass but at the time was viewed as an eccentric echo of the French glass traditions of Emile Galle or Maurice Marinot. Finally, the baby dropped: near the center of America, in Ohio, in 1962, at the Toledo Museum of Art workshops (widely cited as the founding event of studio glass) led by Littleton. This time, the participants used blowpipes without historical association: honest black American iron pipe purchased from a local hardware store, suitable for gathering at one end, blowing from the other. Something new and innocent had entered the world.

But every newborn arrives with genetic baggage. "Philosophically, the earliest things were closest to Abstract Expressionism" Littleton remarks. Later, his own work became simpler, partly in reaction to baroque work that his close friend Erwin Eisch was showing. The adoption of a minimalist approach allowed Littleton to isolate and explore non-functional aspects of the glassmaker's craft: positive and negative forms, minimal cutting, and breakage. Littleton describes this as escaping the container or "sculpture in another way. "Perhaps studio glass--American style-- owes more to minimalism and its roots in constructivism and Mondrian than to abstract expressionism, rooted in Cubism and Picasso. Littleton's prominent student, Dale Chihuly, is best understood as a post-minimalist. As opposed to this, the European extensions of studio glass show marked cubist (think of Libensky-Brychtova, who have been adopted as studio artists by American artists and collectors) and Picasso (think of Eisch) influences.

Reacting to the work of Erwin Eisch was just one indicator of Littleton's need to reinvent himself with regularity: from potter (1950s) to teacher (1950s - 1970s) to founder (1960s) to independent artist (he left teaching in 1976 To devote his energies to creating a body of work in glass") to printmaker and collector who has assembled a notable collection of approximately one thousand pieces of historical and modern glass, ranging from Emile Galle to Raoul Goldoni.

The founder of studio glass hasn't made glass since 1991. He explains: "I stopped at age 70. My furnace had been on 24 hours a day for about 8 years; a tear down [for repairs] was due, and my health was bad. " Now Littleton's health problem--a bad back, one of the things he shares with his two brothers--has been repaired: he has just returned home to Spruce Pine, North Carolina after successful surgery in upstate New York. For Littleton, the possibility of making glass--perhaps of reinvention?-- lingers: in my last telephone interview, he admitted that since his back surgery he has been "a little tempted to pick up the blowpipe."

Today, studio glass, itself a surgical transplant of the furnace from the aesthetically ailing glass factory of the 1950s into the artist's studio, has never been in better health. Has it all played out as he expected? "In my wildest dreams. Still it has a ways to go. For example, there is only one Dale [Chihuly] and there is room for lots more. Dale's success is everybody's. We glory in it. " Chihuly reflects his success back onto Littleton: "Without a doubt Harvey Littleton was the force behind the studio glass movement; without him my career wouldn't exist. He pulled in talented students and visiting artists; I used the same concept when I taught at RISD. Also, Harvey was a big thinker--if he wanted a special piece of equipment, he would spend the money; he taught us to think big instead of thinking small--some of that rubbed off on me. And he encouraged us to be unique--Harvey liked that." One of the curiosities of studio glass is that it has produced both a Littleton and a Chihuly (just one of each), while most art movements are established and led by core groups sharing a related technique and style. Studio glass attracts strong individuals who mark their talents by blazing off from center rather than gravitating toward a common aesthetic or spiritual focus. As Littleton says: "The 'Technique is Cheap' debate indicated we were not so involved in technique but with the result when you turned people loose with this responsive material. Studio glass is unified by material rather than by technique." Perhaps because of this, artists working with glass are somewhat immune from the pressure to conform to a common aesthetic; the focus on material gives them freedom to explore and combine abstract expressionism, minimalism, pop art and other techniques (sometimes with elegant, sometimes with horrifying results). If there is a common aesthetic to studio glass, it is the challenge to transform the material into all known styles.

A striking feature of the founding of studio glass is that Littleton had, by the time of the publication of his book A Search For Form in 1971, cut the template for so much of what followed, beginning with technique. A large section of the book is technical, including photographs showing a glory hole and illustrating how glass is blown; but when he writes that "Glass in the molten state is able to take into solution almost any material; platinum is the major exception." it might be a metaphorical plea for the artist to go beyond technique and to think about dissolving art styles as well, and Littleton goes on to link glass as material to glass as expressive of artistic style by exploring abstract expressionism, minimalism, and the arts and crafts movement in his work.

Littleton sought to recapitulate the history of 20th century glass, writing in 1971 that "My book is both a guide and a revivalist manifesto" and citing a link with "Tiffany and Carder and Galle [who] were trained as artists and had chosen glass, but [who] chose to work within the framework of factories that they founded, factories that were totally under their control so that they made very exciting things...." It might even be argued that Littleton sought long term to put the artist back in control of the factory, even as he sought to put the furnace into the artist's studio. From this point of view, studio glass did not seek to avoid the factory, it rather sought to return artists to control of the furnace--a goal that has been achieved. But there is more. Artist Paul Stankard points out that when he started working with glass-- in a technical glass factory setting--he was "uncomfortable with the strict tolerances required for manufacturing glass apparatus. Harvey nurtured a climate that I thrived in, coming out of the factory." Littleton replaced industrial tolerances (in millimeters) with artistic tolerance.

Littleton even pioneered the evangelical attitude toward promoting the new medium that is a key to its current success. Aware that education is essential for both innovation and continuity, he established the first glass program at a university (The University of Wisconsin at Madison, 1962-3). As a potter, he wondered "why pottery never got off the ground in terms of support. They were selling work in the $5 to $10 range. So, glass needed a support network. I told my students to price their work at at least $100--look at Steuben--and that they should get at least 10 times what potters got. Glass is expensive to make and should be expensive to buy." Today, glassmakers can rely upon the support of an extensive network of museums, galleries and collectors. Harvey Littleton led the way with early successes: a one person exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1963 and, in 1965, the Museum of Modern Art recognized the importance of studio glass by acquiring work.

From our relatively comfortable late 1990s perspective, it is easy to overlook a profound aspect of Littleton's persona: he is a risk taker and adventurer who sailed two boats across the Atlantic (once in 1973 with one other person, and again in 1986, aboard his sailboat "Tamara," with two others). The founding of studio glass may today seem obvious, even conservative, but almost everything about glassmaking is risky and difficult, and in 1962 the outcome was far from assured. To a large extent, Littleton led by force of will. Marvin Lipofsky reports about the period from 1962-4: "As students we didn't know how to do anything. All we could do was emulate what Harvey was doing. We learned how to put the pipe in the glass. It was dip and blow. But what shape should you make? The first time we opened the annealer and looked at our finished pieces, there was an argument over who made what because they all looked alike. But Harvey had the inspiration that artists could use glass as an art material. His thoughts went beyond making vases. It was wide open for Harvey." It was this wide openness that Littleton sought to convey to his students. Despite a tendency to minimize the strength of his will, as when he says that he sought to put glass into the studio because "no one else was willing to take it on," Littleton was well aware that studio glass might dead end: "In glassblowing, if the necessary risk is taken, the outcome must always be in doubt. Artistic creation must occur in crisis." This is the thrill and challenge of the glassmaker's art, forcefully described by Littleton in a language tinted with sexual overtones, driven along as if hunting a wild animal:

"When the artist lifts his blowpipe, he must be prepared to intervene with all his aptitude, training, form-sense, as well as physical and mental energy. Everything he knows converges at once on this curious scene reenacted millions of times in human history: a man breathing his desire into the molten glass. Each time it recurs it is only as different as the men are different from one another; the dance with the blowpipe, the sudden grasping of tools and hissing of steam as they are applied, the form completed--these things remain the same. A man cannot educe forms from hot glass by conceiving it as a cold, finished material. He must see it hot on the end of his pipe as it emerges glowing from the furnace; he must have a sense of wonder! His perceptions are ever new; his reactions must be swift and decisive. He must immerse himself in immediate experimentation and study, for the glass will not wait."

Tom Riley, the director of Thomas R. Riley Galleries, brings this approach into balance when he says: "Harvey added it up very carefully. Risk yes, but not without analysis." Or as Littleton says: "It was a risk, yes, but it wasn't a risk." Glass is like that: Strength and fragility. Risk and containment.

Littleton believes that "art is a strange business because we distill emotions into a form" and strives to make his artwork "intense, personal, direct." The work Littleton created from the mid-1980s onward was a period he considers central to his career as an artist. Again, it is in character that Littleton would take a risk by creating a body of work late in life and placing significant emphasis on its importance. In a recent video, he remarks that: "Whatever title you give me, I stand or fall in the end by my work." In the private collections I have visited that include these late sculptures, they are frequently displayed high up, generally on the top shelf, as if crowning the collection, or in some sense overseeing the artworks by other artists. Perhaps there is another reason for their position as well: in choosing to produce grouped objects that cantilever and balance precariously, Littleton has created a sense of imbalance and fragility. The sliced forms, sprays, and implied and lyrical movements cap Littleton's achievements, elegantly tying together the possibilities of glass as color field, mathematical model, expressive performance and minimal sculpture. They do so while retaining the memory of risk, of a time when the whole venture might well collapse in upon itself.

I have heard glassmakers described as the truck drivers of the art world. Glassmaking is sweaty, gritty, dependant upon solid (but very fragile) objects made with 19th century industrial tools. The presence of a furnace in the artist's studio seems anachronistic at a time when fine art has become post-conceptual, pre-post-modern, disappearingly visual and mordantly intellectual. Norman Mailer might have been writing about this relationship in 1969 when describing the first launch for the moon: "Saturn V was a furnace, a chariot of fire. One could witness some incandescent entrance to the heavens. But Apollo 11 was Command Module and therefore not to be seen. It spoke out of a crackling of static, or rolled like a soup can, a commercial in a sea of television...." Harvey Littleton lit a fire in the artist's studio at a time when the artist's studio was becoming a command module for conceptual art and its academic outposts. Molten hot and computer cool never cohabit in the world of technology, but since Littleton they have had to make an accommodation in the world of art.

Glass as Fine Art

Glass as Fine Art

By William Warmus

In its struggle to be recognized as a new species of art, studio glass has benefited from the recent multiplication of media. Artists (and audiences) have become more adventurous and may even be described as eager to explore and enjoy versatile and unorthodox art materials, whether they are high tech nanotechnology, low tech plywood, or somewhere in between, a place occupied by much work made in glass. The medium of studio glass is characterized by countless styles made in many countries, and so studio artists are inherently comfortable with multiple working approaches (think big factories and tiny blowtorches) and techniques (casting, blowing, engraving). During the early stages of the art, in the 1960s and 1970s, this multiplexing was sometimes seen as a limitation, as if the emergent medium had a flawed, schizophrenic personality. Now it is perceived as a distinct advantage. Glass is called “the new bronze” because of its highly desirable flexibility.

It should also be observed that a chief distinction of glass is that it is member of the small group of transparent and fluid media. The others include water and cyberspace. All three share a “tele-vision” mode: objects embedded in these media can, under the correct modes of manipulation, remain visible at a distance: mistakes are difficult to conceal in such transparent realms. Distances can be artificially compressed, as when a slab of glass is ground into a telescope lens that makes the far seem near, or a stream of energy is coded to transmit an image from one place to another. And a key to the aesthetic of such media is the phenomenon of flotation, that objects embedded within these media defy gravity and appear to float in space, visible from all angles. This rich complexity makes the transparent media very challenging to the artist. They possess an openness, almost a nakedness, that inspires both desire and aggression.

And what sorts of art stories might be told in glass? Almost any type of story artists want, or need, to tell. That is among its chief attractions in an age of relentless artistic invention. And it is not a new role for glass. As a material for artistic expression, glass has long been part of multimedia artworks that seek to reinforce, and even create, legends. The funerary mask of the Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamen is a masterwork of collaboration between the goldsmith and the glassmaker (for example, the inlays around the eyes are a dark blue glass: try to imagine Tutankhamen’s expression without these accents). That was 3500 years ago. By the year one, glassmaking had spread throughout the Roman Empire and beyond, its products intimately familiar to princes and merchants, some of whom were buried in glass cinerary urns. And during the European middle ages, glass became the central medium, in the form of glowing stained glass windows inset into gloomy Gothic cathedrals, for portraying the entrance of spirituality into the heart of mankind. Glass is among the few media capable of transforming light.

Continuing in and expanding upon these venerable traditions, many of today’s studio glassmakers fit perfectly within a world where artists are expected to explore and merge diverse cultural influences. One and the same work might fuse Japanese formalism, Italian technical and color bravado, and American edginess of expression. In particular, it is a thesis of this book that studio glass artists have contributed significantly in four areas of artistic innovation: abstraction, realism, the investigation of natural forms, and what I call stagecraft: the theatrical presentation of artworks to an audience.

Pluralism emerged during the decline of formalism (primarily Abstract Expressionism) in the early 1960s. One of its defining characteristics is the emphasis of context over object: Politics, fashion, psychology, even religion and geography have all become essential elements in appreciating the meaning and quality of the artwork. And the speed with which the artist moves, in the form of adaptability, has become important. In the absence of any one defining style, all styles and all media compete for attention, and the successful artist is the one who can outrun his peers, capture the fleeting attention of the public media and the art public, and then move on to some new innovation or sensation, his new found fame (hopefully) attracting an audience like a magnet.

Despite the attractions of pluralism, some key artists using glass remain unapologetic formalists who insist upon beginning and exhibit clearly articulated boundaries, and that indulge integrity of ending with the art object. They seek to create sculptures that form. The goal is to make something truly beautiful in an old-fashioned way, and to tempt age old desires: the eye’s delight in delicate color, the hand’s hunger for rich texture. Some of this work is not afraid to seem costly and elitist. And some is brittle, fragile, but also defiant and purposefully difficult: ultimately, the audience must find their way to the object itself (a reproduction just won’t do!), stand near to it, look at it or caress it. Formalist art is all about this challenge of appreciating and experiencing a definite object in all its lonely perfection. Formalists are the curmudgeons of the art world, but they can be endearing curmudgeons.

A Brief History of Glass

A Brief History of Glass

By William Warmus

Glass is the buoyant medium. Phoenix-like, it literally emerges from fire and ash (and sand and a few other ingredients) and air plays a central role in giving it shape. Hollowness abounds and is celebrated. The process of making glass can be highly theatrical, the colors available are dazzling to the eye, the final object highly resistant to decay but simultaneously rather fragile, like an aging diva.

The natural history of glass begins dramatically wherever there are volcanoes, whose fiery eruptions emit rivers of molten rock that include obsidian, a darkly colored and highly opaque glass. This precious material was worked by prehistoric and ancient civilizations into a variety of tools—the Roman historian Pliny passes on a legend that mirrors made from obsidian reflected only shadows, not images. Through a glass darkly? In a tremendous reversal of scale, contemporary glass required the development of very small furnaces—portable volcanoes?—so that artists could make glass in their own studios.

It was about 1500-1600 B.C. that the human hand became involved in the direct creation and shaping of molten glass. Archaeologists theorize that the production of ceramics precedes glassmaking and that early glass was almost an accidental by-product of ceramic glazing, which is a glassy process. Glass and bronze or gold are sometimes used together in antiquity [contemporary artist Michael Glancy carries on the tradition], and there is conjecture that they were created in the same workshops, both sharing similar techniques including core-forming. Perhaps the metal oxides that are a part of bronze casting were appropriated by ancient glass makers as coloring agents. When the first objects made purely from glass begin to appear, it is in the Near East and ancient Egypt, where glass was sometimes made from ingots imported from abroad. Much of the best preserved evidence about the role of glass in society comes from the capital city of the Pharoah Akhenaten, known as Amarna, ancient Akhetaten, c. 1350 B.C.

There is evidence to indicate that glass was made at Amarna in what we would today describe as a small workshop setting, such as the excavated compound of the sculptor Tuthmosis. Maybe these ancient studios looked a little like the earliest contemporary glass studios, some of which had dirt floors and primitive glassmaker’s equipment—the log bench and tent that formed the studio in the early 1970s era of the Pilchuck Glass school north of Seattle come to mind. Glass was expensive to produce, requiring large quantities of scarce fuel to fire the furnaces, and required great skill to work while in a molten state. This made glass precious at Amarna, found mostly in association with the Great Palace and owned by Royals. It was considered an elite substance and signifier of status, comparable to gold or silver, and it is probable that the material’s rarity contributed to its prestige. This established a pattern that has been followed continuously: glass remains today among the most expensive artistic materials to create.

Significantly, Egyptian Royalty favored vivid colors in the decoration of palaces and tombs, and the flamboyant and intense colors available in glass vessels and inlays probably satisfied this aesthetic need. Glass was also recognized as an ideal ensemble player that sculptors could use to create complex multi-media works of art. The lapis blue glass inlays in the funerary mask of Pharaoh Tutanhkamen coexist easily within a solid gold matrix. Today, artists like Dan Dailey and Dale Chihuly produce intensely colored, flamboyantly crafted sculptures in workshop settings that would be the envy of the ancient Egyptians.

Ancient Egyptian glass was mostly cast or formed on a solid core, and it precedes the invention of glassblowing. The earliest blown glass objects date from the first century B.C. in the Roman Empire. Blowing is a fast process, and there was something of an explosion of interest in making glass for everything from drinking cups to souvenirs of gladiatorial contests to cinerary urns. Some of these works were signed by the artist who created them, most notably the molded glass vessels of Ennion, a few marked “Ennion made me.” The Romans also excelled at casting glass, producing extraordinary small scale sculptural portraits of emperors and the noble classes. But the technology of the time did not allow for the production of artworks of any scale, for example a head the size of the one by contemporary artist Hank Adams would have been impossible to produce. Maybe that is why ancient glassmaking is sometimes called a “minor” art? But does size really matter in things artistic?

The invention of glassblowing unleashed a rapid development in the medium. As Donald Harden noticed, in writing for The Glass of the Caesars, “There must have been some experimenting before glass-blowing became accepted and well understood by glassworkers... but ...within 20 or 30 years they proved capable of developing almost all the inflation techniques still present nearly 2,000 years later in the workshops of their modern successors.” It is possible to argue that a similar pace of innovation was not again achieved until the “invention” of studio glass after World War II. Artists like Lino Tagliapietra and Dante Marioni are direct successors to the phenomenal masters of ancient Rome.

As Rome fell, traditional glassmaking declined. The Middle Ages would have been a true dark age for the medium, but in reality it was the opposite: stained glass was invented and it satisfied an urgent need for lighted (but also sheltered) space within the great (but at times glacial) cathedrals that were rising throughout Europe. Abbé Suger, who is credited with the development of the Gothic style, thought of stained glass as perfect for symbolizing the entrance of spiritual light into the hearts of mankind. Thus glass became a premier art form, an atmospheric art full of mystery for the most spiritually inclined, a cinematic art capable of telling stories to everyman. Contemporary artist Judith Schaechter has found new ways to merge mystery and atmosphere, and news stories to tell, in her gothic inspired panels.

If the Italian Renaissance saw the revival of, and gradual improvement upon, many of the lost techniques of glassmaking known to ancient Rome, it was the late 19th and early 20th centuries that laid the most direct groundwork for contemporary glass. The Art Nouveau and Art Deco artists Emile Gallé, Louis C. Tiffany, and Rene Lalique, together with the visionary entrepreneur Paolo Venini, collectively explored and experimented with many of the processes and themes that have been adapted by contemporary artists. Nature became a supreme source of inspiration, whether as a dying orchid (Gallé) or a voluptuous Peony Blossom (Tiffany’s lamps). They willed their glass to come to life and flow like lava (Tiffany) or melt like ice (Lalique) and loved accidental effects and the look of ancient weathered glass (Tiffany used bits of ancient glass in his windows). Small parts were composed into gigantic wholes (Tiffany’s windows for churches, Lalique’s outdoor fountains) or details were made so microscopically small that their effect became decadently precious and dreamlike (Gallé). All four were masters of the ensemble and stagecraft nature of glassmaking, assembling skilled teams of individuals to execute their ideas, sometimes employing famous architects and sculptors as designers (Venini enticed the architect Carlo Scarpa to create handsome designs in fused glass).

But glassmaking—especially glassblowing—is a difficult art to learn and the equipment required to make it is expensive. By the time of World War II, the traditions of artistic glassmaking were in danger of evaporating: Louis C. Tiffany, our nation’s premier artist using glass, had been dead since 1933 and his work long out of fashion. Glassmaking with artistic pretensions had been replaced by “industrial design” as practiced in factories. What to do?

Some consider the founding event of contemporary glass to be the creation by Harvey K. Littleton, in 1942, of a small glass sculpture representing a nude female torso. This was not done in the confines of an artist’s studio but within the high technology Vycor Multiform laboratory at Corning Glass Works (now Corning Inc.). Like many founding events that later evolve into organized and complex systems, it contains none of the accretions that have come to define studio glass today: the artist was not alone in the studio, in fact the “studio” was a scientific laboratory, about as far away as you can get from the spirit of the artist’s realm. And Littleton considers the first work he made there an unsatisfactory object, not a work of art. It certainly has the appearance of a derivative copy, appropriated from an ancient classical model, and made from a figure Littleton had shaped first in clay. Littleton’s progress in glass was interrupted by his service in the Army Signal Corps during World War II, but he kept up his work on glass intermittently thereafter, always with the goal of encouraging more aesthetic experimentation among glassmakers, and a subsequent torso cast in 1946 became the his first exhibited work. By 1962 Littleton was able to conduct a series of workshops (with scientist Dominick Labino and others) at the Toledo Museum of Art that are generally thought to mark the birth of studio glass.

What makes the 1942 object significant is that Littleton willed it into being, in the process anticipating the trajectory of contemporary glass. It was a point of conception, even if the gestation period was 20 years long. The rest would come later: the small furnaces (1962), the educational programs (1960s and 1970s), the museum and gallery exhibitions. Perhaps Littleton’s willfulness is the defining aspect of the contemporary glass movement—artists using glass are not noted for their reticence! Littleton, a Corning native, was perhaps influenced in this regard by Frederick Carder, the founder of Steuben Glass, who was something of a rebel and very strong willed.

Today we appear to have come full circle from Littleton’s earliest attempts to free art from industry, as artists (and not just those using glass) are ever more intent upon exploring the connections between art and science and technology, producing artworks that appear to have emerged from laboratories or factories, even as the appropriation of imagery from any age, era, or culture is accepted as an authentic method of art making. Glassmakers have been doing this—well, virtually forever—and so it is satisfying to see that the trajectories of the various parts of the art world are at last intersecting in fruitful ways.

It took Littleton until the 1960s to pull together all the basics that truly define studio glass: dependable studio scale furnaces and an educational curriculum to turn aspiring youngsters (among them Marvin Lipofsky and Dale Chihuly ) into glass artists, and to keep turning them out in mass, hopefully forever, all over the world. This movement was paralleled in Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic) by the pioneering teacher-artist pair Stanislav Libensky and Jaroslava Brychtova. An independent-minded Czech artist, Frantisek Vizner, working under Kafakesque conditions during the cold war era, succeeded in producing a series of vessels as perfect as anything ever made by human hands.

Logos for Use on Materials

Logos for Use on Materials

Download and save logos for the 50th Anniversary Celebration of Studio Glass. Right-click on any logo to download it in its respective format. Or download the zip file of all three formats.

Featured Glass Art Videos Intro

Featured Glass Art Videos Intro

The video "Pioneers of Studio Glass" was produced by WGTE Public Media for the Art Alliance for Contemporary Glass. It is a fascinating look at the 1962 Toledo Workshops where Harvey Littleton and Dominick Labino first experimented with making glass outside of the factory setting. You can purchase the DVD of this video for $10 (includes shipping). Mail your check, payable to AACG, to AACG, 11700 Preston Rd., Ste. 660, PMB 327, Dallas, TX 75230. Please include the name and address to which the DVD should be sent. Call AACG at 214-890-0029 with any questions.

Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of Studio Glass 2012

Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of Studio Glass 2012

The year 2012 marked the 50th anniversary of the development of studio art glass in America. To celebrate this milestone and recognize the many talented artists more than 160 glass demonstrations, lectures and exhibitions took place in museums, galleries, art centers, universities, organizations, festivals and other venues across the United States throughout 2012.

The year 2012 marked the 50th anniversary of the development of studio art glass in America. To celebrate this milestone and recognize the many talented artists more than 160 glass demonstrations, lectures and exhibitions took place in museums, galleries, art centers, universities, organizations, festivals and other venues across the United States throughout 2012.

The video "Pioneers of Studio Glass" was produced by WGTE Public Media for the Art Alliance for Contemporary Glass. It is a fascinating look at the 1962 Toledo Workshops where Harvey Littleton and Dominick Labino first experimented with making glass outside of the factory setting. You can purchase the DVD of this video for $10 (includes shipping). Mail your check, payable to AACG, to AACG, 11700 Preston Rd., Ste. 660, PMB 327, Dallas, TX 75230. Please include the name and address to which the DVD should be sent. Call AACG at 214-890-0029 with any questions.

Also in honor of the 2012 50th anniversary of Studio glass, as part of SOFA Chicago's 2012 lecture series, AACG sponsored two panel discussions that have been posted on You Tube.

Panel 1, with moderator Tina Oldknow, included Marvin Liposfky, Mary Shaffer, Jack Schmidt and Joel Philip Myers. Click here to see the panel on You Tube.

Panel 2, with moderator Ferd Hampson of Habatat Galleries Michigan, included Mark Peiser, Toots Zynsky, Fritz Dreisbach and Henry Halem. Click here to see the panel on You Tube.

A Visual History of Glass Intro

A Visual History of Glass Intro

Click any image to see a full sized version. Use the arrows to browse in a slideshow manner.

The usage or duplication of these photos is limited to glass exhibitions or programs occurring in 2012 in honor of the 50th anniversary of studio glass, unless further written approval is obtained from the Art Alliance for Contemporary Glass. If you need a high resolution version of any of these photos, please send your request to admin@contempglass.org or call AACG at 214-890-0029.

Art Alliance for Contemporary Glass Key Messages and Q&A

Art Alliance for Contemporary Glass Key Messages and Q&A

Basic AACG 50th Anniversary Key Messaging:

- Next year marks the 50th anniversary of the development of the contemporary glass art, also known as studio glass. To celebrate this milestone and recognize studio glass artists, the Art Alliance for Contemporary Glass (AACG) has initiated more than 100 glass art demonstrations, lectures and exhibitions in museums, galleries, universities and art centers across the country to take place throughout 2012.

- American Studio Glass art began with two glass workshops held at the Toledo Museum of Art in 1962. The workshops were taught by Harvey K. Littleton, who, along with scientist Dominick Labino, introduced a small furnace built for glassworking that made it possible for individual artists to work in independent studios. Glass programs were then established by Littleton at the University of Wisconsin, at the California College of Arts and Craft by Marvin Lipofsky, and later at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), led by artist Dale Chihuly, to name but a few.

- Since 1962 the art of glass has been incorporated into art education, museums, personal collections and many indoor and outdoor installations. Glass is now accepted as an important medium within fine art.

- The AACG Grants Committee is accepting grant requests for 2012 anniversary projects. The next deadline is September 1, 2012.

AACG 50th Anniversary Q&A:

Q: Why is AACG celebrating studio glass art in 2012?

A: The year 2012 marks the official 50th anniversary of the development of contemporary glass in the United States.

Q: What will be going on during the events nationwide?

A: Participating museums, galleries, art centers and other venues are inviting everyone to enjoy contemporary glass art and experience the passion and history behind the glass as art through demonstrations, lectures and exhibits. While each celebration occasion will be different, all events are guaranteed to be among the best places to see, learn about and perhaps purchase glass art.

Q: Who are the artists and organizations participating in this year-long, nationwide celebration?

A: A listing of 2012 glass art events is ever changing and as information is finalized can be found online at [url=http://contempglass.org/event/2012-celebration]http://contempglass.org/event/2012-celebration[/url].

General AACG Q&A:

Q: What is AACG?

A: AACG is a not-for-profit organization whose mission is to further the development and appreciation of art made from glass. AACG informs the public, including collectors, critics and curators, by encouraging and supporting museum and art center glass exhibitions and public programs, and regional collector groups.

AACG is an organization consisting of a board and advisory board that meet together bi-annually.

Q: Who Belongs to AACG?

A: Members are primarily collectors of contemporary glass, mostly from North America but also from Europe, Australia and New Zealand, among other international locales. AACG members also include art galleries, artists, schools and museums. Membership is open to anyone interested in contemporary glass.

Q: Where can I find more information about AACG?

A: For more information including grant applications, online galleries, artist profiles, upcoming events, and more, please visit [url=http://contempglass.org]http://contempglass.org[/url].

2012 Studio Glass Events and Celebrations

2012 Studio Glass Events and Celebrations

Below is a list of the current and upcoming events celebrating studio glass in 2012. Check back often for updates and additions.